Mermaids and Mako Sharks in Monterey Bay?

Seven years—that’s how long I’ve been playing in the waters of Monterey Bay. It’s also how long it took to see my first shark, up close and personal! Unbelievable, right? Maybe not.

Growing up in southern California, I was one of those lucky kids who had never known the need for neoprene wetsuits, booties, or gloves—the average water temperature in sunny San Diego is 72°F (22°C). Sure the water got colder in the winter, but even then, it was always swimmable with a bathing suit. So, you can imagine my shock and subsequent dismay when I first stuck my feet into the chilly beach shallows of Carmel By the Sea in 2008 (average water temperature of 63°F, or 17°C). That cold, harsh water and those rough, rocky conditions were off-putting to the landlubber I had become in my 20-years away from the ocean, so I didn’t discover the magic of Monterey until my second move back to the area in 2011.

When I came back to the Monterey Peninsula, I was ready, or rather determined, to infuse my life with all things ocean. I donned my first wetsuit and took my first SUP excursion, paddling around the wharf and marina with sea otters and harbor seals closer than I had ever dreamed, and out around the jetty into the open waters with sea lions and jellyfish galore. That’s all it took. I was instantly hooked on the magic of SUP and neoprene! Since then, I’ve had the good fortune to play all over one of the most biologically rich and diverse marine environments on the planet, from Monterey to Santa Cruz, and I even learned how to surf in the tumultuous and unpredictable waves of this rugged coast. Why, oh why didn’t I learn this sport when I was younger and had the primo conditions of southern California in my backyard? Perhaps, because girls didn’t surf back then and it never occurred to me that I could do more than boogie board and body surf? Uggg.

Aware that sharks are always out there, lurking nearby like a nightmare stalker, I did what any other dedicated surfer does: kept a weather eye out for pointed dorsal fins, diving seabirds (indicators of schooling fish—aka prey), fish jumping out of the water (to evade predators beneath the surface), and prayed for dolphins and other good-omen critters to show up and instill me with a false sense of security. Dolphins protect humans, right? And surly if there’s a seal nearby, there can’t be any sharks in the vicinity, because it would know and take off! In short, I waded in for a watery workout and hoped for the best.

On our most recent SUP excursion, my daughter, Savvy, and I were happily paddling, about 200-feet (ft) (or 61-meters (m)) offshore, where the water is deeper and cooler, to evade the red tide. Red tide is a typically harmful algae bloom that occurs when water temperatures are abnormally warm, calm, and low in nutrients, which creates oxygen-depleted zones that can cause fish die-offs, or in some cases, produce toxins that rapidly move through the food web, affecting everything from, “zooplankton, shellfish, fish, birds, marine mammals, and humans that feed either directly or indirectly on them.”1 Savvy was tracking slightly behind me and to the left as we skirted a patch of kelp, when I heard her very calmly and distinctly say, “Mom, there’s a shark behind us.”

It took a second or two for my mind to fully process her words and their implications as I, equally calmly, turned my head, coming to full alert, my eyes panning the surface of the water around her, while my legs softened to maintain balance and my hands tightened around my paddle, preparing to act if necessary. My mind protested her words, simultaneously hoping she was wrong, expecting to see something that might look sharky, without being a shark, and imagining what we would do if it turned out to be one of the numerous great whites recently reported in the vicinity with increasing regularity. Worse yet, my imagination quickly conjured one of the great white behemoths I’d just been reading about in a fantastic book called The Devil’s Teeth, by Susan Casey. I guess I already had sharks on the brain and maybe that’s why we finally had this rare encounter.

My eyes landed first on Savvy, still erect on her board, looking a bit hesitant but clearly bracing herself mentally and physically for trouble. A mixture of mom-relief and adrenaline began trickling through my blood, as I continued my assessment of the situation. My gaze moved past her, taking in every square inch of the water around her, and landed next, on a patch of kelp floating at the water’s surface, less than 20 ft (6 m) away. Right beside the kelp, a smooth, softly curved, triangular dorsal fin, roughly the size of my hand, protruded with slightly jagged ridges along the trailing edge. My mind quickly matched her words to the vision behind us, confirming that it was indeed a shark, and not a sea lion, seal, or dolphin.

“She wasn’t kidding,” I thought, at a seemly slow pace for the occasion. I wouldn’t expect Savvy to jest about something as serious and potentially deadly as a shark, on the water or off, especially given her keen knowledge about local sightings, and her own relatively fresh encounter with a dying juvenile mako that had washed up on a local beach. Having been in these waters for seven years without ever seeing hide nor fin of a shark, I guess I was a little skeptical.

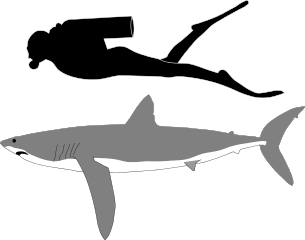

In the few precious seconds during which I observed the shark fin, I came to several rapid, if erroneous conclusions (I learned a lot, post-sighting, including its most likely identification): the shark was moving at a relaxed pace, perhaps more curious than aggressive (makos are the fastest sharks in the world, and can sustain speeds of about 20-miles-per-hour (mph) (that’s 32-kilometers-per-hour (kph) for my European adventure lovers) with shorter bursts of up to 46 mph!2 (74 kph)); based on the smallish size of its dorsal fin and the lack of girth displacing the water around it, it was not a behemoth (the average size of a shortfin mako is 10 ft, 300-pounds (lbs) (or 3 m, 136-kilograms (kg)), with many individuals over 12 ft and 1,000 lbs (3.6 m, 453 kg) having been caught by fishermen, and whereas the longfin mako seen below has a larger dorsal fin, shortfin makos have a relatively small dorsal fin compared to body size); and due to the orientation of that smallish fin, the shark was indeed moving in our general direction, and had probably been following us, for who knows how long.

Longfin mako shark compared to average human. By Kurzon – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23819009

I wish now, that I had kept my eyes on it longer, seen more of its body with my “scientific” eyes, but my instincts told me that I needed to complete a full 360-degree visual of the waters around us, to make sure it was alone, to make sure my daughter was still okay, and to evaluate the best course of action given our location and its proximity. Of course, standing on a paddle board doesn’t lend itself to quickly rotating my body to complete the periscopic action needed, without rocking the board and perhaps falling off at an inopportune moment, so I quickly turned my head the opposite direction, to complete my sweep.

By the time my eyes returned to the last known location of the shark, it was no longer visible. I don’t know which emotion was stronger; the relief of not seeing it, which allowed me to hope that it was gone, or the worry that if I couldn’t see it, I wouldn’t know if it was stalking us, about to attack. I know now, that makos are a pelagic (deep ocean) species that generally attack their prey from below without revealing themselves, aim for the rear, and mostly consume boney fish like tuna and billfish, as well as blue sharks, dolphins, and the occasional squid or sea turtle. They rarely attack humans unless provoked (there are only eight unprovoked attacks on record, and two that were fatal3), and most human injuries occur when fishermen pull makos onto boats as bycatch or for sport hunting (I’ll explain these terms later).

When Savvy suggested that we paddle toward shore to get “out of its territory,” I quickly concurred, instantly proud of her cool response, and we both turned east, paddling just a little harder than before, careful not to lose our balance or splash excessively. We both kept a vigilant watch on the water around ourselves, and each other, matching our pace, so that we would be near each other if the situation worsened. Did I mention the immense mom-pride I felt as we paddled to shore, discussing our observations and our next actions?

During the few minutes it took to paddle to the small surf break near shore, Savvy explained that she had seen the tail protruding from the water (though I had not) and believed it was either a shortfin mako, or a salmon shark, both species being spotted regularly in the area and closely related. We each confirmed that we hadn’t seen further evidence of the shark’s presence, and concluded that our visitor had most likely headed towards the cement ship, a known feeding area. We got out of the water briefly, so Savvy could report the sighting to a local state park ranger, who likely forwarded the information to the “shark chopper,” (a helicopter that patrols the peninsula, looking for shark hazards for swimmers and surfers) which showed up soon after.

On shore, we watched the horizon for a few minutes, to see if the shark would reveal itself again, but it never did. We got back in the water and reversed course (away from the cement ship and the whales we’d been hoping to spot), paddling north to where we had put in, and finished the day without further incident, though we did see two large manta rays, a healthy-looking sea lion flagging a pectoral fin (sticking it out of the water to collect heat from the sun) to regulate its body temperature, and a couple of seals loafing in the kelp beds. We even paddled back out beyond the red algae bloom to take a quick dip in the ocean and cool off. I suspect that we both needed that dunk to prevent “shark fear” from taking too deep of a hold on us—like getting back on a rock wall after you take a fall.

Seeing my first shark was unexpected, humbling, and a bit exciting, so of course the experience prompted me to do some research to figure out which species we saw, and learn about it. While I had harbored an inkling that the fin was akin to a great white (a close cousin of the mako), Savvy had been correct in her first assessment—it was a perfect match to a shortfin mako, a warm-blooded species found in all oceans of the world, with a preference for deep, temperate and warm oceans (typically at Pacific Rim latitudes from Oregon to Chile, and most commonly, offshore from my old stomping grounds—San Diego). I confess to feeling a small sense of relief that it wasn’t a great white shark behind us, because most of the behemoths observed in the Farallon Islands,4 less than 80-miles (18 km) north of our location, were quite willing to attack a surf board (typically shaped like their favored prey) until they learned that it wasn’t as tasty as a sea lion (and SUP boards are basically glorified surf boards). To be fair, the scientists studying the great whites were themselves on a boat no larger than some of the sharks they observed, and their boat was not attacked, but they were in fact using surf boards as bait to study great white feeding behavior.

I remember telling myself and Savvy, “I don’t think a small shark would attack something larger than itself,” hoping to quell our fears while we were on the water. Her responding look was dubious, and I laugh now at the memory. Since our SUP rentals were around 11 ft (3.3 m) long, it seemed illogical that a six-foot shark (my best guess at its size based on the fin) would hunt something nearly twice its size. I have since learned that I was very wrong. In fact, makos are known, second to great whites, for attacking boats of various sizes, though under vastly different conditions. While great whites may bite a surf board, SUP, or kayak to “expore” its potential as food, makos have really only been known to damage a boat when they are pulled on board to be killed, at which point, they fight aggressively for their survival, but rarely win. Who can blame them for trying?

Shortfin mako.

By NOAA-PIRO Observer Program [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

While world-wide commercial fishing continues to deplete many of the most sought after species like bluefin tuna, yellowfin tuna, cod, and salmon (check out the Seafood Watch program from Monterey Bay Aquarium6), it also impacts sharks, dolphins, and other large animals that depend on those species for food, or are caught unintentionally, or in some cases, where valuable habitat is destroyed through unsustainable practices. Sport fishing of “dangerous” sharks and swordfish has also become very popular around the world, further impacting many species populations which are already in decline.

But fishing is not the only cause of the decline. “There are now 405 identified dead zones worldwide, up from 49 in the 1960s,” according to David Biello,7 of Scientific American. Dead zones, areas in which oxygen levels are so low that they cannot support life, are caused by pollution from agricultural runoff and fossil fuel consumption, resulting in massive die-offs and catastrophic environmental damage. Most of these dead zones occur along the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts of the United States, the Atlantic Coasts of Europe, and the Pacific Coasts of Asia and the United States. Add to this the fact that, “more than 80 percent of the radioactivity from the damaged reactors ended up in the Pacific,”8 from the Fukushima Nuclear Plants that still threaten to meltdown as a result of the March 2011 tsunami and earthquakes, and you might start to realize just how serious the threat is to our oceans, the organisms that inhabit them, and the humans that depend on them for everything from food, to oxygen (most oxygen around the world is produced by algae in the ocean, rather than trees on land), and recreation.

Shortfin makos, the 5th most deadly shark, and great whites, the deadliest shark, per Planet Deadly,9 can’t compete with humans for top billing as the apex predator of today. They and their environment are in serious jeopardy, which also affects the balance of all other organisms in their food web. So, what can we do about it?

- Share information with your friends and family by sharing this article via the social links below.

- Follow the links in the bibliography below, and read the articles to be even more informed.

- Eat only sustainably caught seafood.

- Avoid consuming overharvested species.

- Make efforts to reduce consumption of fossil fuels.

- Reduce fertilizer runoff into local streams that eventually run to the ocean.

- Reject the building of additional nuclear power plants along the volcano, earthquake, and tsunami prone “ring of fire.”

- Get involved at your local level in ocean conservation, plastic prevention, wildlife protection, or whatever aspect of the environment you feel most passionate about.

Remember, we’re all part of the same closed system! Whatever effects the survival of shortfin makos, eventually affects the survival of us all.

Bibliography

1 – Harmful Algae & Red Tide Regional Monitoring Program. http://sccoos.org/data/habs/abouthabs.php

2 – Nancy Passarelli, Craig Knickle and Kristy DiVittorio, Florida Museum of Natural History. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/fish/discover/species-profiles/isurus-oxyrinchus/

3 – Molly Edmonds & Patrick J. Kiger. http://animals.howstuffworks.com/fish/sharks/most-dangerous-shark1.htm

4 – Susan Casey, The Devil’s Teeth, A True Story of Obsession and Survival Among America’s Great White Sharks. Henry Holt & Company.

5 – Mike Rogers. https://www.sharksider.com/shortfin-mako-shark/

6 – Seafood Watch, Monterey Bay Aquarium. http://www.montereybayaquarium.org/conservation-and-science/our-programs/seafood-watch?gclid=CjwKEAjwu7LOBRDZ_MOHmpW6kW8SJABC19sYP05JQGcQROcMdm6f9RM4fw1iPZvyyKBC8jjDoM5rDRoCO8vw_wcB

7 – David Biello, Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/oceanic-dead-zones-spread/

8 – Ken Buesseler. http://www.pbs.org/newshour/updates/fukushima-radiation-continues-to-leak-into-the-pacific-ocean/

9 – Planet Deadly. https://www.planetdeadly.com/animals/dangerous-sharks/2

This was very educational and nicely introduced by sharing your earlier personal experiences in the surf and sand.

Thanks for your comment! I had a lot of fun experiencing and writing it, and plan to write similar posts about other animals I have encountered first hand in the ocean.

Wow good blog, Good information combined with a good story. Sharks are scary but they are also beautiful creatures that need and deserve our protection.

I couldn’t agree more with you about the sharks. Thanks for your comment! ANd please share the blog with your friends using the social media tags under the story!